On 22 October 2022, Giorgia Meloni became the first woman Prime Minister of Italy. This fact became rather obscured by Meloni’s past. At the age of fifteen she had joined the youth wing of the neo-fascist Movimento Sociale Italiano party (MSI) and had been actively engaged in its activities. The MSI dissolved in 1995 and formed the Alleanza Nazionale (AN) that marked a break with the MSI’s fascist past. However, in April 1996 as a member of the new party, Meloni told French television: ‘I believe Mussolini was a good politician. That is to say, everything he did, he did for Italy. And you don’t find that in the politicians we’ve had over the past 50 years.’

Meloni’s career however continued to progress. In April 2016 she was elected to the Chamber of Deputies. The AN since November 2004 had been part of a coalition government led by Silvio Berlusconi, and in 2008 she was appointed Minister of Youth in Berlusconi’s fourth government. By then the AN had merged with Berlusconi’s Forza Italia to form Il Popolo della Libertà. Reflecting tensions and rivalries within the Italian right and a certain marginalisation of the AN within Berlusconi’s ‘super party’, Meloni formed with some colleagues Fratelli d’Italia (FdI) in 2012, drawing members largely from those with an AN background. Over the next decade, with Meloni as leader from 2014, the FdI built up support such that at the October 2022 elections it became the largest party with 26% of the votes and 30% of seats in the Chamber of Deputies. It was seen as the most far right government in Italy since World War Two, but subsequently there has been considerable debate about where exactly to place the government on the political spectrum.

Political scientist Davide Vampa in a recent in-depth study argues that the FdI-led government will represent a radical populism with strong conservative nationalist leanings, but which will not resurrect interwar fascism. Indeed, the government is cautious in outlook as it faces domestic and international constraints. Much of the FdI’s appeal rests on Meloni’s charisma. The FdI-led government so far represents nothing particularly exceptional in terms of what is happening elsewhere in several European countries. Indeed, it is not significantly out of line with many Italian governments formed after the demise in the 1990s of the parties that formed the basis of Italy’s post-1945 Republic. But there is a stronger component of sovereigntism emphasising taking back control of the nation from internal and external threats. In this vein the government has engaged sovereigntist policies such as bans on laboratory grown meat and the use of foreign terms in official communications.

Meloni has sought to manage the neo-fascist connection of herself and some of her party’s members by saying that fascism has been ‘handed over to history.’ However, she has defended rather than decried the MSI despite the fact that she could have put her involvement down to youthful indiscretions. She has nonetheless sought to clamp down on those in her party who are ‘nostalgics’ for Mussolini’s fascism, but some of her ministers do have form in that regard. Crucially, her presentation of her government’s aims has shied away from any fascist content, emphasising a commitment to democracy and international alliances.

The question is therefore ‘will this continue?’ Historians such as Paul Corner and Spencer Di Scala still see the spectre of Mussolini’s fascism hanging over Italian politics with certain politicians and journalists propagating a distorted picture about the true nature of that regime. This includes those in and around Meloni’s government. Like Meloni, two of her coalition’s co-leaders have presented a noticeably benevolent view of Mussolini’s rule. In 2003 Silvio Berlusconi told The Spectator that Mussolini ‘did not murder anyone’ but sent them ‘on holiday to confine them’ and did not need to resort to mass repression because he ‘was very popular.’ La Lega leader Matteo Salvini in 2016 contended that Mussolini did many good things until he introduced the Race Laws and went into alliance with Nazi Germany. The good things included the false claims that Mussolini introduced old-age pensions to Italy and that his social security system was better than that proposed by the then government of Matteo Renzi.

Nonetheless, there is the possibility seen in a number of European countries that populism can shift in an authoritarian direction with a hollowing out of democratic institutions, curbs on freedoms and adoption of a robust sovereigntist outlook. It seems unlikely, however, that Mussolini’s fascism would play a significant part if this were indeed to happen in Italy. The first reason is that the fascism of the imagined nostalgic past is based upon a mythical representation, some of it simply the hangover of Fascist propaganda. Fascist Italy was a police state, where political violence and repression were prevalent, there were numerous interventions to regulate the personal lives of citizens, regime policies benefitted those with wealth at the expense of the mass of Italians and the state was increasingly organised to pursue international expansion. The reality of Mussolini’s fascism does not seem to be a plausible or attractive offering in today’s Italy. Meloni, or other rightist leaders, would struggle to maintain their appeal if they went down such a road. As with Mussolini’s fascist state, considerable force would be required to put in place such a system.

A second reason is that Mussolini’s appeal may not actually be that widespread. A survey in 2019 reported that 48.2% of the Italian population favoured the need for ‘a “strong man in power” who does not have to worry about Parliament and elections.’ This was taken by many to reflect a nostalgia for Mussolini, but a poll a year earlier found that 60% of Italians had a negative or very negative opinion of him compared to 19% who had a positive or very positive opinion (the remainder for various reasons not expressing a preference). Subsequent surveys have shown similar results. The coalition government of Mario Draghi, whose collapse led to the election bringing Meloni to power, was highly popular which suggests that many Italians want something different to the fragmented and unstable party system that perennially leads to a weak executive, not some form of dictatorship. Thirdly, as Meloni is aware, Italy is very dependent upon its European neighbours. Any move in a fascist direction would strain and probably break such relations with high costs for the country. Finally, Meloni is located like many others of the right in populism. Her strategy is fundamentally populist, not fascist. As historian Federico Finchelstein notes, populism firmly rejects pre–Cold War fascism’s version of dictatorial rule, while many observers of populism argue it is an importantly different type of political system from fascism.

This still leaves the question of whether Meloni’s populism will shift towards authoritarianism and intolerance internationally, rather than a resurrection of fascism. During the 2020 election, Meloni announced her intention to replace the Italian parliamentary Republic by introducing a semi-presidential French-style Fifth Republic in order to give institutional stability and effective decision-making powers to the executive. Apart from whether this should be labelled authoritarian, there is the point that any constitutional change in Italy faces a notable constraint because it requires a popular referendum that can only happen with a two-third parliamentary majority in support. This is well short of the governing coalition’s majority with its 43.8% share of the vote. The Italian constitution, designed with the intention of preventing a strong executive as Mussolini had put in place, has many checks and balances including an independent judiciary, and a president with an important role and powers to match. It is hard to see how Meloni can fundamentally break free from the institutional nexus that has stymied her predecessors. At the same time, the billions of euros provided by the European Union’s Resilience and Recovery Facility and RePowerEu funds would make it difficult for any Italian leader to fall out seriously with the EU for the next three years. However, EU policies on debt reduction and migration will generate tensions. More broadly Meloni, who is highly astute politically, in all likelihood wishes to establish the FdI as the main right-wing force in Italy. This will be aided by the decline of La Lega and Forza Italia but requires some leaning towards the centre which makes any break from the Western Alliance unlikely.

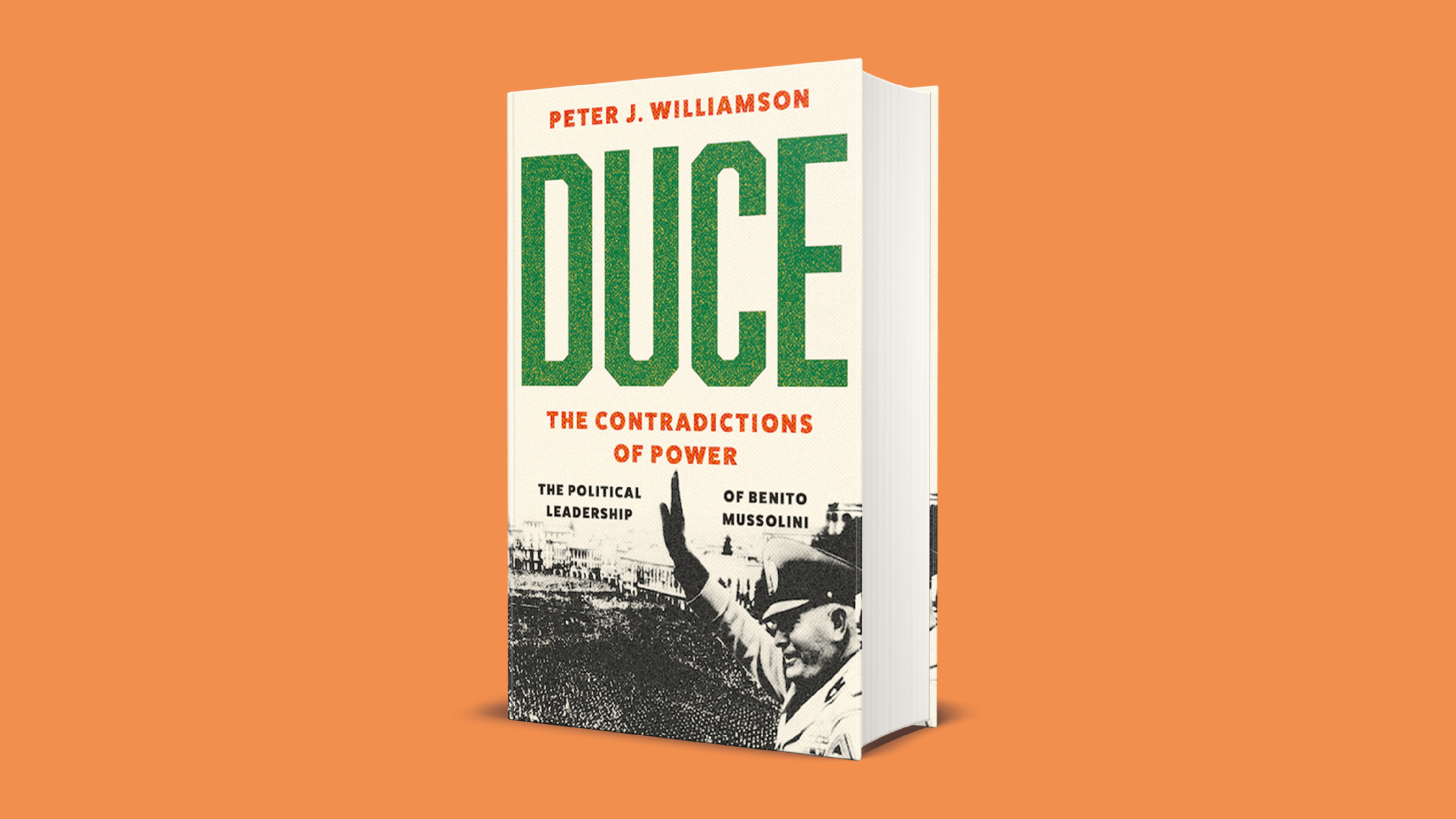

In my book, Duce: The Contradictions of Power, I presented a regime under Mussolini that is different in many important respects from what the new Italian government is proposing. Making links to fascism may have a shock impact, but it would be better to see what is happening in Italy through the perspective of modern populism and the insights it offers and the issues it raises. That said, Duce also highlights the gulf between the reality of fascism and the perspective held in certain circles. Why this should be so is difficult to pin down, but after its fall Mussolini’s fascism became the object of a dispute between right and left in Italy that had more to do with contemporary politics than history.

Peter J. Williamson is a former scholar of political science and public policy (1980-91). His previous book Varieties of Corporatism covered Mussolini's corporatist system, and he has retained an interest in Italy's dictator since. He has also worked in the NHS and government at board director level in Scotland (1991-2014).