I was boarding my flight to Mogadishu a few months back when a Somali friend sent me a short, ominous text message.

“Make sure they don’t announce what time you’re speaking.”

It was a well-meant, practical warning: when in Somalia, keep the lowest possible profile. Try not to get caught up in the bombings, assassinations and sieges that still plague Mogadishu and (twenty five years after the country first plunged into chaos) prevent it from shrugging off its reputation as one of the world’s most dangerous cities. Don’t get carried away, in other words, by the idea that Somalia is on the mend.

I settled into my seat with a familiar surge of adrenalin kicking at my ribs, trying to read the expression of the ethnic Somalis – members of a giant, global diaspora – shuffling past me down the plane’s aisle.

What made them think Mogadishu was now a safe bet to visit? When can you tell that a country has properly, unquestionably turned a corner? How do you balance a patriotic desire to help rebuild with an instinct for survival?

These are disorientating times for those who fled Somalia in an exodus in the early 1990s. Some wars end with a peace treaty. Some countries, like South Africa in 1994, get an historic election to mark the moment that those in exile are finally welcomed home.

But the men and women boarding my flight in Istanbul had no such reliable signposts. Instead they were obliged to sniff the wind and judge, from a succession of fragile moments – militants retreating, governments installed, pirates thwarted – whether their country’s slow, uneven journey away from chaos had reached some sort of critical mass. Or whether the Islamist militants Al Shabaab, or some fresh disaster, would ruin things once again.

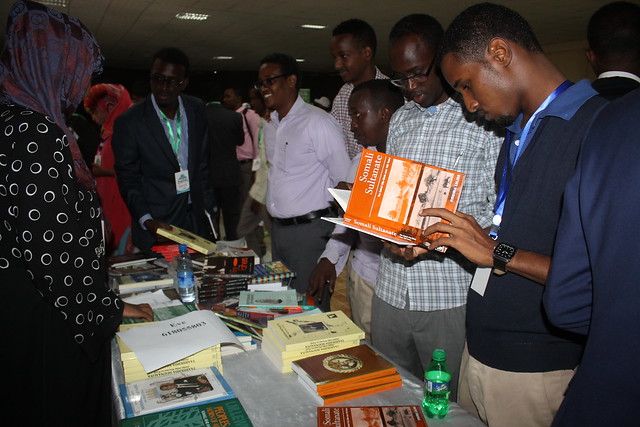

Over the course of 15 years visiting and reporting from Somalia, I’ve seen plenty of reasons for pessimism. But the specific event I was attending in Mogadishu fell firmly into the “positive” column. It was something out of the ordinary, something, indeed, rather wonderful. A book fair. A proper event at a big Mogadishu hotel, with its own hashtag, and panel discussions — a cultural milestone for a ruined capital that had not experienced anything like it for a generation; not since the old government collapsed in 1991 and a lovely port city of open-air cinemas, beaches and cafes was ground into the dunes. A beguiling sign, surely, that Somalia’s bad old days might indeed be coming to an end.

A few hours later I strolled through Mogadishu’s imposing new airport terminal, met up with my designated security escort – eight armed guards in a pickup – and headed through the traffic to the heavily fortified City Palace Hotel (hotels have been a particular focus of attacks in recent months).

On stage, in a bright yellow banqueting hall, in front of perhaps five hundred Somalis, a young woman from the United States was explaining that this was the first time in her life that she’d been “home” to Mogadishu. And she loved it. “I never want to leave,” she half-shouted, and the crowd clapped like evangelists welcoming a new recruit, held their phones in the air, and updated their social media accounts with yet more photos of a city which, they insisted, was being reborn.

It was hard not to be impressed, to be carried away by the almost fanatical optimism in the room. Hard, but not impossible.

In the crowded courtyard outside the hotel banqueting hall, I heard a voice shouting out my name.

“It’s crazy here!” said Ilham Gassar with a grin. She’s a tall, energetic women’s rights activist who fled Somalia with her family in 1992 when she was 7 years old. She grew up in north London, and has the accent to prove it.

I first met her in 2012, just after she’d made her first trip back to Mogadishu. The visit had not gone well.

Within hours of arriving in the city with relatives, Ilham’s brother had been threatened at gunpoint. That night she’d learnt that gunmen were actively searching for her in the city’s hotels. In the morning it was confirmed there was a “legitimate threat” on her life. She fled to the airport, reached the departure gate, and began to relax.

But minutes before she was about to board her plane, an immigration official came over and confiscated her passport. Then he tried to push her back out into the city, presumably so the gunmen could have another opportunity. After some frantic phone calls and the intervention of the United Nations, Ilham was kept safe and flown out of Somalia the following morning.

“I came very close to losing my life. I felt numb,” she told me soon afterwards. Not least when she discovered why she’d been targeted. It was, she says, the work of powerful members of her own sub-clan – clans are a central part of Somali society – who had simply assumed Ilham had come back with plans to run for their allotted seat in the new parliament. And having jumped to that conclusion, they took what for them had become the next logical step.

“There is no loyalty. No moral ground,” Ilham said, bitterly, of the people who’d stayed behind in Mogadishu during the years of anarchy — a sharp contrast with those who’d fled. “We value human beings more than money.” She swore she’d never return to Somalia.

But that was 2012.

When I saw her at the book fair this August, Ilham said she’d finally had a change of heart and that she’d returned to spite those who’d once chased her away. “I thought, to hell with them! This time I’m actually going to run as an MP,” she said gleefully.

I asked her if she thought it would be safer now and she said she’d spoken to the elders in her sub-clan and patched things up, to some extent, although she asked me not to mention any names here in case “it gets them upset again.”

Later, in a guesthouse overlooking the airport runway and the turquoise Indian Ocean, Ilham explained how she and other educated members of the diaspora were determined to come back to Mogadishu “with a different mindset.” They had grown up in stable western democracies, able to appreciate the value of institutions, and were anxious now to prove that politics in Somalia could be done differently, free of corruption and clan divisions. Even if that meant Ilham had to leave her husband and three young sons at home in London. “If you can help a nation to stand on its feet, why not?”

I flew out of Mogadishu a couple of days later.

A few weeks after that, Ilham spoke to me by phone. “It’s crazy here,” she said, as usual. But this time there was no enthusiasm in her voice. Presidential and parliamentary elections were due – are still due – after a string of delays. But they won’t be the proper one-man-one-vote polls that had once been promised, and Ilham had just decided to withdrawn her candidacy. She said she’d come to realize that the system remained utterly corrupt, that prospective MPs, mostly the same old faces, were busy paying huge bribes – figures of up to $1.3 million have been reported – to get selected. They would then expect to recoup that from whomever they picked as President.

“I wanted to make a point,” she said, but she feared that if she continued her campaign she would be tainted, or worse. “It’s all about money… I didn’t want to drown in the sea.”

But Ilham has decided not to give up on Somalia for a second time. Instead she’s got a new job as a political advisor at the United Nations office beside the airport, and she’s thinking of bringing her family from London to nearby Nairobi, Kenya.

“It’s not safe enough to move them back here yet. But maybe next year.”

It would be naïve to think that Somalia’s relatively wealthy, educated diaspora could sweep back into a broken nation and fix its problems. The country has changed too much in their absence. But the determination of people like Ilham is heartening, and a broader lesson also seems clear.

At a time of mass migration, conflict, and growing xenophobia, it is worth remembering that Somalia’s diaspora has, for a generation now, sent some $1.6 billion a year back to relatives struggling in the Horn of Africa – a lifeline that dwarfs all foreign aid to the country. And now thousands of people like Ilham – a UK taxpayer who has grown up in a (broadly) tolerant, sophisticated democracy – stand ready to go “home” to Somalia to fight for those same values. Politicians promising to build walls and calling for new restrictions on refugees from places like Syria might want to take note.

Andrew Harding has worked as a foreign correspondent for the past twenty-five years in Russia, Asia and Africa. He has been visiting Somalia since 2000. His television and radio reports for BBC News have won him international recognition, including an Emmy, an award from Britain’s Foreign Press Association, and other awards in France, Monte Carlo, the United States and Hong Kong. He lives in Johannesburg with his family. He is the author of The Mayor of Mogadishu: A Story of Chaos and Redemption in the Ruins of Somalia, published in 2016 by Hurst. He tweets at @BBCAndrewAfrica