Once believed to be islands of prosperity, tranquility and security, peace in two Gulf states was recently shattered by sectarian terrorism. In Saudi Arabia Shia mosques were targeted in three attacks on places of worship, killing several Shia worshippers. Then terrorism moved to Kuwait in an appalling suicide bombing of the Imam Sadiq mosque. The common factor in these ghastly events is that the perpetrators are Saudis, and that they timed their attacks to coincide with Friday communal prayers, thus maximising the number of casualties and impact. So far, Bahrain, Qatar, UAE and Oman have escaped this round of violence, despite the presence of Shia minorities among their populations, but the recent spillover of sectarian killing to Saudi Arabia and Kuwait may spread to other Gulf countries too.

Such terrorism is not an export from the Levant to Saudi Arabia and its neighbours, but rather the return to its historical home of an indigenous trend of political violence. The justification for such sectarian terror was established in Saudi Arabia, where it has its ideological roots and has since seized the imagination of a new generation. It is thus unsurprising that the perpetrators were Saudis. ISIS is not simply a problem unfolding in the Levant but is in part an outcome of religious indoctrination and political conditions in Saudi Arabia.

Too much ink has been spilt over the contribution to terrorism of Wahhabi teaching, especially its uncompromising rejection of the Shia as true Muslims. This rejection is exemplified by Saudi preachers’ recent denunciations of people they dub as the sons of temporary marriage (a Shia practice unacceptable to most Sunnis), majus and rejectionists, all pejorative names currently in use, especially on online sites such as Facebook, among many public and anonymous hard line preachers.

There is no doubt that hate preachers are an entrenched reality in Saudi Arabia. This is not a new phenomenon that was initiated by ISIS but is an important cornerstone of the Saudi-Wahhabi religious tradition. It flourished in the eighteenth century and continues to inflame the imagination of a wide circle of clerics and their followers today. In an attempt to preserve their exclusive monopoly over truth and faith, Wahhabi preachers rely on old medieval Sunni religious texts produced under different historical circumstances to theorise complete rejection of the Muslim Other, a category that includes not only religious minorities but the vast majority of other Sunni Muslims, such as Asharites and Sufis.

So it is time to confirm that today the discourse of hate that inspires sectarian wars is a truly Saudi phenomenon. This reality cannot be disputed given all the available evidence to hand. Any observer who seeks to deny this is either ignorant of the history of the country or simply absolving the perpetrators of any responsibility.

But this is not the whole story, and nor can it explain why Saudis are engaging in terror inside their own country and among its Gulf neighbours as well as exporting terror abroad, to the Levant and beyond the Arab world. The ideology of terror is nourished by domestic political conditions specific to Saudi Arabia itself. Without these conditions the ideology cannot continue to inspire such acts. In fact these conditions are the key to understanding why many young Saudis have become the footsoldiers of contemporary sectarian violence.

The political conditions that nourish the ideology of sectarian terror are many and have been forged by the Saudi regime itself, which thus finds itself in the position of an accomplice in generating successive waves of terror in recent decades. First, the regime has sought to establish a monopoly over religious thinking in the kingdom since its creation in 1932 in order to distinguish itself as a state of monotheism. This monopoly privileged the most radical interpretations of Islam in all educational institutions and the judiciary, thus bringing up a generation whose religious knowledge is limited to the most radical interpretations of Islamic theology.

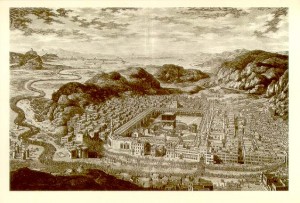

Second, the Saudi regime eradicated theological diversity and knowledge in places as important as Mecca, where several Islamic schools of religious interpretation had been established for centuries. Young Saudis are introduced to this diversity and are immediately asked to denounce and reject it. Hence, many doctoral dissertations in Wahhabi institutes of learning focus on how other Muslims have erred, deviated and subverted Islam. Students are often encouraged to engage with the discourse of other Muslims only with the objective of demonstrating their heresy. At lower educational levels, such as in schools, younger students are simply required to learn and memorise ‘evidence’ against the Muslim Other.

Most terrorists do not embrace a sophisticated approach to rejecting other Muslims by dint of pursuing a doctorate in Islamic studies but are simply absorbers of hate speech, most of it emanating from preachers on the payroll of the Saudi regime as teachers and educators, or readers of ancient and new Wahhabi fatwas, published in fancy bound leather volumes. Today these have been supplanted by short treatises published online, easily accessible and costing nothing. They travel fast domestically and globally with minimum effort. Of course it would be ridiculous to hold the Saudi regime responsible for the religious opinions of all clerics in the country. However, it is enough to hold the regime responsible for the opinions of its own religious functionaries whose salaries it pays.

Third, the Saudi regime is responsible for eliminating all spaces where the youth can debate, challenge, and offer diverse and alternative interpretations that differ from the dominant sectarian state religious tradition. Recently, a judge employed by the regime sentenced Raif Badawi to ten years in prison and 1000 lashes simply for creating a liberal online forum where young Saudis might engage with ideas other than those that revere the Wahhabi tradition. Thus the mildest critique of the Wahhabi tradition is immediately interpreted as ‘insulting Islam’, and punished severely in the Saudi courts.

Another example of repression of any initiative challenging state sponsored interpretations of Islam, this time in relation to the issue of human rights, is the case of the lawyer Walid Abu al-Khayr, founder of a discussion forum initially known as Sumood, but re-launched as Monitor of Human Rights in Saudi Arabia.

Abu al-Khayir was brought before the Specialized Criminal Court in Riyadh on 6 October 2013, on charges that included, among other things, ‘breaking allegiance to and disobeying the ruler’, ‘disrespecting the authorities’, ‘offending the judiciary’, ‘inciting international organisations against the Kingdom’ and ‘founding an unlicensed organisation’. The Wahhabi judiciary is determined to protect the regime from criticism and its own monopoly over the interpretation and application of Islamic law, as such cases make clear.

While Wahhabi denunciation of other Muslims is undeniably responsible for the recent sectarian terror in the Gulf, the Saudi regime’s hidden agenda, which privileges such a bigoted and radical interpretation of Islamic texts, should not be discounted. Without Riyadh’s support and the power of the petrodollar, Wahhabi theology would have remained a radical fringe interpretation of Islam, without a judiciary to defend it. This symbiotic relationship explains why the regime pays the bill for the propagation of Wahhabism domestically and internationally and criminalises its opponents.

Radical religious movements often emerge on the periphery of societies, seeking refuge in remote and inaccessible regions, but with Saudi state support the radical Wahhabi movement has become a central and privileged tradition that seeks to eliminate any rival trends threatening its monopolistic control of Saudi society, and defends state repression of all non-violent activism.

The Gulf states have witnessed the onset of this latest wave of Saudi sectarian terror, one that is grimly familiar to countries like Kuwait, which early in the twentieth century built a wall to protect its nascent city-state from Saudi-Wahhabi intrusions. Today, fortified borders may not suffice; rather, the Gulf states should act collectively to put pressure on Riyadh to reconsider its support for one of the most radical movements in Islamic history.

Dr Madawi Al-Rasheed is a visiting professor at the Middle East Centre at the London School of Economics and Political Science. She has written extensively about the Arabian Peninsula, Arab migration, globalisation, religious trans-nationalism and gender. She is a columnist for Al-Monitor. Her next book, Muted Modernists: The Struggle over Divine Politics in Saudi Arabia, will be published by Hurst in October.

On Twitter: @MadawiDr