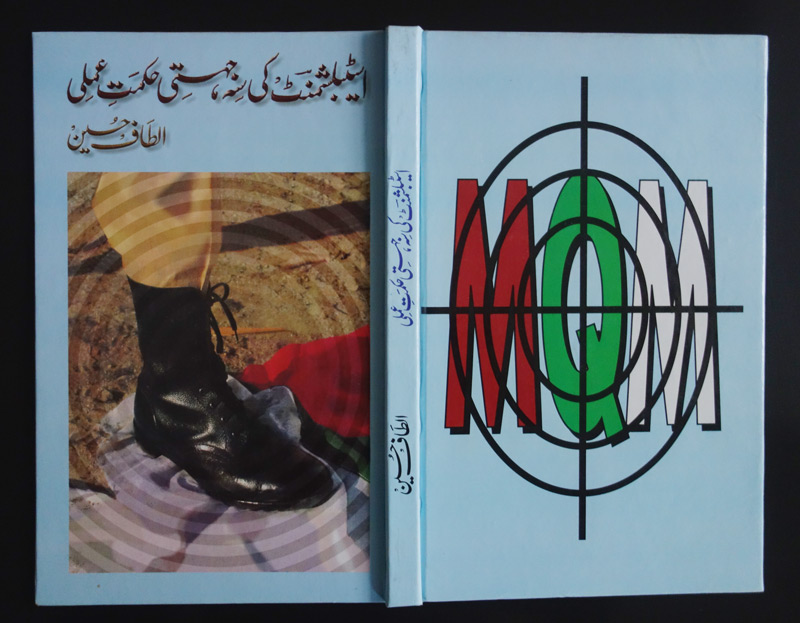

In the early hours of 11 March 2015, a heavy contingent of hooded paramilitaries raided ‘Nine Zero’, the headquarters of Karachi’s largest political party, the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), as well as several nearby houses. In the hours that followed, the Rangers (a paramilitary force operating under the authority of the federal government but commanded by military officers) recovered dozens of weapons allegedly stolen from NATO containers – a claim immediately rebuffed by the MQM and the US State Department – and arrested around sixty party workers and cadres. MQM workers present at the time, some of them armed, initially tried to resist the invasion of their turf. Although they did not open fire on the Rangers, the latter discharged rounds into the air to disperse the crowd. A young cadre of the MQM, Waqas Ali Shah, lost his life in the general confusion that ensued – probably to a stray bullet, although this remains contested.

What is certain, however, is that ‘the Rangers had done their homework’, as a party worker of the MQM who witnessed the raid told me a few hours later. The paramilitaries were obviously well informed, which led to the capture of several individuals whom they presented as notorious ‘target killers’. The biggest catch was a middle-aged man known as Faisal Mahmood, alias ‘Mota’ (Chubby), who was sentenced to death in abstentia in 2014 for his involvement in the murder of journalist Wali Khan Babar in 2011. Others allegedly detained during the raid included Farhan Shabbir (alias ‘Mullah’) and Umair Siddiqui, who had long been suspected by the Karachi police of heading two of the most active hit squads operating under the command of the party. These allegations and Siddiqui’s ‘confession’ in front of an anti-terrorism court a few days later were rejected by the MQM leadership, however, which accused the Rangers of trying to ‘malign’ the party.

The pressure on the MQM shows no sign of abating. A few hours after the raid, an anti-terrorism court announced that the MQM’s most notorious prisoner, Saulat Mirza – who has been sitting on death row since 1999 on charges of murder – would be executed on 19 March. Neither this announcement nor the morning raid on ‘Nine Zero’ came out of the blue. Since September 2013, the MQM has been bearing the brunt of a police and paramilitary operation aiming to restore normalcy in the crime-ridden port city. While army officials have repeatedly claimed that the on-going operation does not single out any particular group, the MQM thinks otherwise and claims that its workers are regularly ‘disappeared’ or eliminated in ‘fake encounters’ with the Rangers.

In the weeks preceding the 11 March raid the MQM also found itself at the heart of a major public controversy after an investigative report prepared by the Rangers – which was leaked to the local press – suggested that party officials were involved in the deadliest factory fire in Karachi’s history. Although this hastily prepared report will probably not survive the close scrutiny of Pakistani courts, it did stir controversy. By alleging that the 2012 Baldia factory fire (which led to 257 deaths) was a reprisal attack against recalcitrant entrepreneurs who refused to cough up ‘protection’ money (bhatta) to the MQM, the report revived old polemics surrounding the party. And unlike in the past – when the local media used to shy away from laying charges against the MQM for fear of reprisals – this time local scribes endorsed somewhat uncritically these serious allegations. This only reinforced the plausibility of the charges levelled against the MQM in the eyes of the general public, fuelling moral outrage against the party even before these charges could be verified.

For all the army’s self-professed commitment to impartiality, it remains to be seen whether the on-going operation is truly aimed at ‘restoring the writ of the state’, or instead provides yet another example of partial refereeing, where the most powerful organ of the state stops short of pacifying society, content with arbitrating between politico-military forces through a mix of selective repression and inherently unstable compromises with momentary protégés. The army seems to have learnt from its past mistakes. Unlike in the 1990s, when it waged an all-out war against the MQM and Mohajirs at large (Urdu-speaking ‘migrants’ from North India who settled in Pakistan after the 1947 Partition), the military currently follows a more targeted strategy. It seems to believe that the MQM can be ‘cleansed’ of its criminal elements, and that its alleged militant wing can be dismantled for good. This is easier said than done, however. As the party worker quoted above suggested menacingly a few hours after the raid, the Rangers (read the army) can detain or kill all the ‘target killers’ they want: for each one of them, ‘two more are created or born to take revenge. It’s like a ticking bomb’.

The army – and you can’t really blame it for that – reasons in military terms. But police and paramilitary operations can only patch things up – and often aggravate the situation. The durable pacification of Karachi, for its part, will require considerable political acumen and a fair judicial process – both of which have been tragically lacking in the past. Once again, the government of Nawaz Sharif seems to have surrendered to the army while thinking that it was serving its own short-term interests: the raid on ‘Nine Zero’ was duly approved by the government, which might have used this opportunity to teach the MQM a lesson after the latter refused to support the candidate of the ruling Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) for Senate chairman. Such petty politics can only escalate the crisis. One can only hope that both the PML-N and the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), which is currently governing the province of Sindh, will now re-engage with the MQM and bring it back on board the democratic ship, instead of using the army to settle old accounts. Whether its detractors like it or not, the MQM remains the fourth largest political party in Pakistan, and by far the largest in Karachi, Pakistan’s economic and financial hub. It also remains a military force to be reckoned with. While certainly down, it is far from being out. Pushing it further against the wall will only marginalise the more moderate elements within its leadership, and reactivate its sense of victimisation and militant posturing. MQM leaders and workers alike have always intoxicated themselves with fantasies of apocalyptic showdowns. Reviving these fantasies – many in the party are already talking of an upcoming ‘civil war’ in Karachi – would be a dramatic mistake.

Laurent Gayer is a researcher currently posted at the Centre d’études et de recherches internationales (CERI)–Sciences Po, Paris, and author of Karachi: Ordered Disorder and the Struggle for the City.