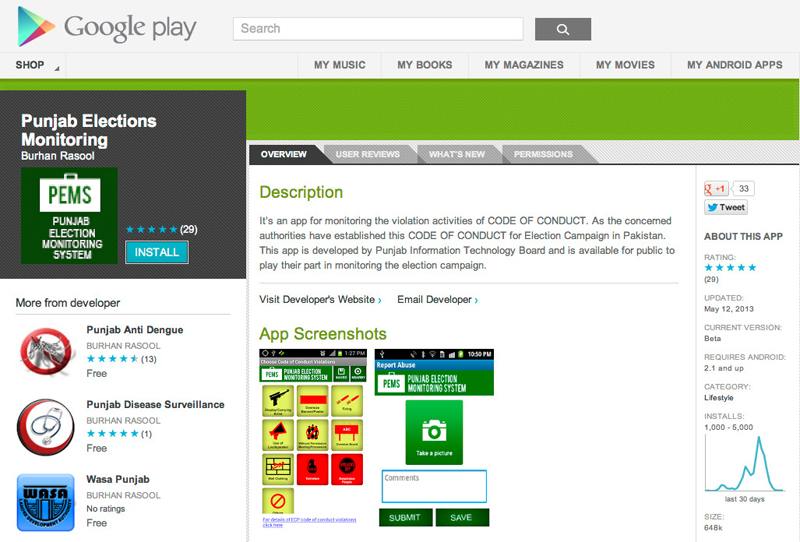

In the recent Pakistan elections, 15,000 observers equipped with smart phones and a custom-made Android application were part of the efforts to run a fair and free poll, Jon Boone reported in The Guardian. The app, based on a similar program for reporting dengue fever, gave the observers the ability to notify election authorities with one touch of a finger that a particular type of malpractice was in progress in a precise place. (See picture above).

Around the world there is endless speculation about the effects of digital technology on electoral politics. In the US, both the Obama presidential campaigns used the Internet and mobile phones not just to raise money but also to identify supporters and get them to the polls.

From South Africa to Japan, politicians and organizations put new verbs into action: they Tweet often and ‘friend’ every voter who will friend them back. By the time of India’s next general elections in 2014, the country will have an estimated 120 million Facebook users, about the same number of people as voted for the Congress party in the elections of 2009.

Political organizations and governments focus big money on hi-tech methods to hook up with voters, influence them and win them over.

But in places where elections sometimes have qualities of elections in Dickensian England (well-liquored voters and well-muscled coercion), it’s Small Tech, not Big Tech, that makes a difference on polling day. And Small Tech needs to be in the hands of active people motivated to use it.

It’s unclear how much effect the election-monitoring app had in Pakistan in May 2013. But the mass use of mobile phones for political organization and fair elections got its big start in South Asia with the 2007 elections in India’s state of Uttar Pradesh (UP), as we tried to explain in The Great Indian Phone Book (pp. 246-58).

It was Small Tech on thousands of basic 2G phones that proved potent – along with the highly motivated people at both ends of the phones.

In 2002, India had 7 million mobile phones. By 2007, it had about 150 million. The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), an organization based on Dalit (formerly “untouchable”) support, had been built by its founder, Kanshi Ram, on a cadre of dedicated workers. Many of them were in low-status jobs in the government, especially Indian Posts and Telegraphs (IP&T). They learned early about mobile phones, and by 2007 many hard-core BSP workers had mobile phones which they happily wielded for political work.

BSP strategists finessed an improbable electoral alliance with Brahmins, the highest of castes. But BSP grassroots activists first had to be convinced of the value of such an alliance and then had to sell the idea – that Dalits and Brahmins should vote for the same candidates – to voters at 120,000 polling booths.

At a great many of those booths, the BSP had “captains,” responsible for mobilizing the 1,000 or so voters registered at each booth. In the past, to have communicated even with devoted workers and keep them apprised of day-to-day events would have been impossible. But cheap 2G phones enabled the central leadership of the party to move information up and down the chain constantly. In a low-turnout election, the BSP got its supporters out to vote and won a surprising victory.

And, as in Pakistan in 2013, the mobile phone played another role. It allowed observers to identify malpractice and quickly and accurately inform authorities with a call, a text message or sometimes a picture. The crucial part of the mix is motivated people – committed party workers and diligent officials with the power to enforce a strong code of electoral practice. In this respect, India is fortunate. Unlike many Indian institutions, the Election Commission remains honest, respected and powerful.

Mobile phones by themselves have not changed elections. By the 2012 UP elections, all parties had cottoned on to the tool, and the BSP after five inglorious years in government was roundly defeated.

What did the election suggest about technology? The Congress Party, with plenty of money and hi-tech but not many fired-up followers, did poorly, managing to increase its share of the total vote by only three per cent to 12 per cent. But the election had the highest turnout in UP history as every party worked on the formula of “identify your supporters, get them to the polls and use technology to try to do it.”

This is not Big Tech – vast data-bases and sophisticated algorithms. It’s Small Tech, and Small Tech requires motivated people. Cheap mobile phones provide people with a new ability to coordinate with each other, get rapid access to lawful authorities and create new possibilities in democratic elections.