This article is taken from issue one of a new quarterly publication ‘Critical Muslim.’

This article is taken from issue one of a new quarterly publication ‘Critical Muslim.’

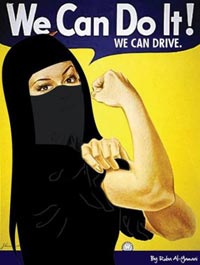

It is a truth universally observed that women drivers exist to be scorned, belittled, demeaned and abused. I know—I used to be a woman driver! It is a fascinating curiosity that Saudi Arabia manages to conform to this principle by the singular expedient of preventing women from driving at all.

I have often wondered what it is about vehicular transportation that induces irreducible and ineradicable misogyny. In these sensitive days— post the men are from Mars, women from Venus debate—one is supposed to be more subtle than just to put it down to testosterone. If the androgenic hormone is not responsible, then what is it that makes the internal combustion engine the great redoubt and ultimate legitimisation of male supremacy?

Whatever the cause, it now appears that should this bastion of male pride be humbled in Saudi Arabia a new dawn of human liberty will be assured. Then the spring of Arab awakening will be made high summer by bevies of black shrouded women independently driving themselves to an infinite array of shopping malls or bustling around on a host of domestically-related tasks. This will be prelude to a new world order in the realms of social, economic and political power. Once this iconic pinnacle of indivisible liberty and human rights is secure then all manner of things will be well in the best of all possible worlds.

Actually, I beg to differ. While liberty may be indivisible, it is surely the case that not all freedoms are of equal moment. There are distinctions to be made concerning essentials. There are what might be termed required rights and those rights which are a nice bonus, should circumstances allow and make available their enjoyment. In other words some rights are contingent; they will inevitably follow if the basics have been put in place. In this order there is a battle cry of freedom, an inherent agenda. And according to this perspective the freedom to take charge of a motorised vehicle is, quite simply, tangential to human dignity, not least because it is entirely dependent on one’s ability to afford a car in the first place—by no means a universal state of affairs. Where, I wonder, does it say that all people are created equal to own a motor car? God help the planet if they ever get round to legislating that clause.

There can be no question that the Saudi insistence on debarring women from driving is wrong headed. It relies on an infantilisation of women combined with a demonisation of their supposed sexual potency. In reality it is an empowerment of male weakness which actually sustains, nay encourages, positively unhealthy attitudes to human relations. A moment’s reflection suffices to confirm it has nothing to do with Islam, except as a perverse misreading of Islam’s inherent ethic of mutuality and balance in gender relations. It comes down to customary practise and an obscurantist inability to come to terms with change.

Once again Saudi Arabia and its peculiarities are being hyped around the world. It is not merely a question of the bizarre nature of this imposed and policed limit to freedom. It is a function of the global fixation with the fate and state of Saudi women. Muslim women the world over perennially find themselves caught in the crosshairs of this fixation. The supposed archetype of Islamic authenticity we are forever encountering is a stereotype framed by the idea of Saudi women. The sisters of Saudi have a lot to bear—but they also have a lot to answer for, to Muslim women who lead very different lives and struggle to vindicate very different attitudes and ideas about Islamic gender relations.

Clearly, I am in the category of one conflicted and unconvinced by the mould breaking nature of the ‘day of rage’. According to the estimable Jason Burke in the Guardian, the outrage led some forty Saudi women to take the wheel. A breathless global media waited, watched and relayed more detail than seemed warranted.

Surely, I hear you think, my failure to rally to the spirited determination of these Saudi women verges perilously close to an anti libertarian stance. Once again I beg to differ. I am fully cognisant of the thin end of the wedge theory of freedom. Indivisible as liberty is, its course, so it is argued, must be inexorable, wherever one starts. Claim one liberty, no matter how small, and change will happen. A single blow for any liberty must eventually let freedom ring loud and clear everywhere. The trouble is I cannot think of or imagine anywhere or any time when this theory has been practiced or put to the test.

Surely, I hear you think, my failure to rally to the spirited determination of these Saudi women verges perilously close to an anti libertarian stance. Once again I beg to differ. I am fully cognisant of the thin end of the wedge theory of freedom. Indivisible as liberty is, its course, so it is argued, must be inexorable, wherever one starts. Claim one liberty, no matter how small, and change will happen. A single blow for any liberty must eventually let freedom ring loud and clear everywhere. The trouble is I cannot think of or imagine anywhere or any time when this theory has been practiced or put to the test.

My own experience of Saudi Arabia consists of being confined to what effectively became a zenana (cell) with some twenty Saudi women for the duration of a conference. Instead of discussing conceptual aspects of social policy and issues about broadcasting, as advertised and according to the papers I had prepared, at the behest of outraged members of the Saudi ulema I found myself discussing ‘Women in Islam’ with a hastily assembled gaggle of Saudi sisters. It was not a pleasant experience. I challenge anyone to have one single strand of escaped hair rudely pushed back under one’s scarf while in the act of praying, because such flagrant disregard was supposedly irreligious, and not wonder who is victim and who willing, indeed zealous, collaborator with obscurantism.

In the privacy of our secluded conferring there was scant evidence of any questioning of custom and tradition, or indeed any thinking about the meaning and potential of interpretation of religious text. There was, however, a great deal of screeching, running, scrambling for shrouds and hiding whenever a waiter (male of course) arrived with our food. Using the hotel restaurant was deemed inconceivable by the Saudi ulema and, I must say, by my fellow conferees.

As a broadcaster commissioned to report to the world on the conference, my life was not made easy. I ended up luring the great and the good of the global community of Muslim scholars and intellectuals to my hotel room and sitting them on my bed to record interviews. Perversity has its rightful reward in the entirely contrary outcomes it produces. It is a measure of the regard for such nonsense that no luminary thought the location contrary to dignity or the decency of either party, and none therefore refused to be interviewed under these circumstances.

Nor would I try to suggest that all Saudis are clones of their ulema. Indeed, I came to suspect the Saudi organiser of the conference either had psychic powers of precognition or had fitted me with a GPS device years before they were invented. Whenever I made furtive escapes from the female quarters to go about my professional business I invariably encountered our host. He would plant himself resolutely in the middle of the corridor and engage me in loud conversation for as long as possible, interrupted as frequently as could be by introducing me to every passing notable. It was a heroic tour de force, only stopping short of challenging or indeed overturning the ridiculous ruling of the ulema. And there you have my problem in a nutshell.

Today Saudi women are educated. Many further their education abroad in western institutions, just as Saudi men do. Saudi men and women travel extensively around the world. There is no lack of awareness of how different everywhere else is to Saudi Arabia. While women everywhere, in the supposedly liberated and enlightened West as well as across the diversity of the Muslim World, have endured and continue to endure discrimination and misogyny in multiple overt and covert ways, the difference in attitudes and outlook let alone custom and practice cannot be lost on any sentient Saudi. The willingness to frame their protest at the driving ban within the bounds of tradition, to stir without shaking the status quo is exactly what gives me pause.

Today Saudi women are educated. Many further their education abroad in western institutions, just as Saudi men do. Saudi men and women travel extensively around the world. There is no lack of awareness of how different everywhere else is to Saudi Arabia. While women everywhere, in the supposedly liberated and enlightened West as well as across the diversity of the Muslim World, have endured and continue to endure discrimination and misogyny in multiple overt and covert ways, the difference in attitudes and outlook let alone custom and practice cannot be lost on any sentient Saudi. The willingness to frame their protest at the driving ban within the bounds of tradition, to stir without shaking the status quo is exactly what gives me pause.

Dedication to liberty and freedom does not just happen to counter inconvenience. Its surest hold on human aspiration is through reflection, analysis, and debate about the quality and condition of social, economic and political life. It is founded in moral force and suasion that is extensive and all embracing in its understanding and aspiration. Without such a context driving a car, whether the driver is male or female, is merely getting from one place to another. The resources to think and question are available in Saudi Arabia. Gradualism is a perfectly acceptable course of reform. However, gradualism shades into complicity with the comforts afforded by the system when it fails to entertain a general critique of the essential constituents of human dignity, liberty and freedom.

As things stand there is precious little evidence of a gathering groundswell of such thinking taking place in Saudi Arabia. Too little evidence, I fancy, to invest the actions of forty women behind the wheel of their cars as a harbinger of a new future. In the general scheme of things it is more of a distraction, and one that is not disinterested, from the serious life and death cries for basic and essential freedoms being undertaken elsewhere in the Middle East.

I was once a woman driver. I have foresworn the internal combustion engine on grounds of exorbitant cost and environmental detriment. I have opted for the inestimable pleasures of being conveyed door to door without the hassle of navigating through unfamiliar streets, finding parking spaces, paying parking fees and then walking half a mile to my desired destination. As a result I have been freed from the unprintable epithets hurled through passing windscreens and the unseemly gestures made in my direction. I have liberated myself from misogynist road rage and feel absolutely safe from any danger of thinking or acting like a Saudi woman. And that, dear reader, is why much as I urge them to freedom, I am not enthralled by Saudi women drivers as a rational summons to liberty.

© Merryl Wyn Davies, 2011