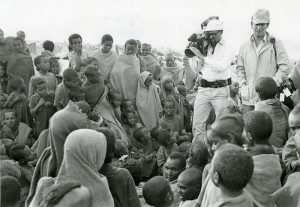

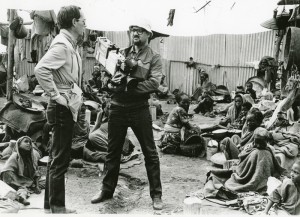

On 23 and 24 October 1984, BBC Television news broadcast a series of reports about a famine in Ethiopia. The story led both the lunchtime and the early evening 6pm bulletins on BBC1 and ran on each occasion at six minutes or longer—which was remarkable for a foreign news story set in a developing country and without any British angle. The footage was re-cut and featured later that evening on the BBC1 Nine O’Clock News, viewed by an audience of 7.4 million. Over the following days the news images from Ethiopia, shot by a Kenyan based Visnews cameraman, Mohamed Amin, and presented by the BBC South Africa correspondent Michael Buerk, were seen by almost a third of the adult population of the UK. At the same time it was re-broadcast by many hundreds of TV stations across the world, including the American network NBC, where it featured prominently on Tom Brokaw’s evening news show. The footage contained harrowing images of starving people of all ages who were arriving in their thousands at feeding stations in northern Ethiopia.

The first report, transmitted in the bulletins on 23 October, opened with a wide panning shot across a group of desperate famine victims, who had congregated on the outskirts of a town in Tigray. The commentary began:

Dawn, and as the sun breaks through the piercing chill of night on the plain outside Korem, it lights up a biblical famine, now, in the 20th century. This place, say workers here, is the closest thing to hell on earth. Thousands of wasted people are coming here for help. Many find only death. They flood in every day from villages hundreds of miles away, felled by hunger, driven beyond the point of desperation. Death is all around. A child or an adult dies every 20 minutes. Korem, an insignificant town, has become a place of grief.

Michael Buerk’s reports from the Ethiopian highlands, broadcast on BBC TV news in October 1984, were to become landmark news items. John Simpson, the BBC’s World Affairs editor, considers that ‘The famine in Ethiopia was probably the biggest news story BBC Television News broadcast in the 1980s, until the fall of the Berlin Wall.’ It acted as an international siren telling the world about the plight of the famine victims in Ethiopia, and eventually spurred on the biggest humanitarian relief effort the world had ever seen and a spectacular new strand of raising funds and awareness.

Yet the question remains, why did this particular coverage become so significant, and what were its wider implications both for institutions and attitudes towards giving, as well as the dilemmas of humanitarian intervention? The coverage of the Ethiopian famine, because it had such profound effects, is significant both in itself and as a historical case study that illuminates much wider problems. It was an example of a huge and worldwide news event, but one which ultimately involved major misunderstandings and misconceptions. Despite the multiple myths and assumptions that have since arisen, there is substantial evidence to indicate that the media perception of the famine in Ethiopia was far from accurate. But this was not the only famine that was misunderstood. In preceding and succeeding years there have been other occasions in the reporting of the developing world (and in particular Africa) where in hindsight the media also got things badly wrong. So the media coverage of the Ethiopian famine needs to be seen in a wider context, because it played a pivotal role in how Western countries have understood and reported Africa in the latter part of the twentieth century. It also had an unexpected and transforming effect upon private charitable institutions in the West. And largely as a result of the extraordinary response to the media coverage, foreign relief NGOs grew at an unprecedented rate and their relationship with the media was radically and permanently altered.

Suzanne Franks is Professor of Journalism at City University in London and author of Reporting Disasters: Famine, Aid, Politics and the Media.