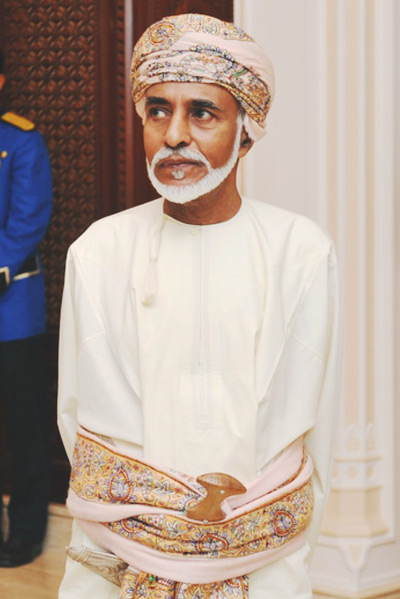

Sultan Qaboos’ visit to Germany for medical reasons in July 2014 has revived concerns across Omani society for the future of the country without the ‘father of the nation.’ On 5 November, A 4-minute address on state channel Oman TV by Sultan Qaboos, looking emaciated and announcing that he would not be able to come back to Muscat for the National Day celebrations two weeks later, only temporarily reassured Omanis and implicitly confirmed rumours of cancer that have been circulating in the Gulf since July.

Sultan Qaboos (r. 1970) has no children and has not publicly designated an heir in 2014. The principles of succession to the throne are formalised in Articles 5 and 6 of the Basic Law of the State, promulgated by royal decree in 1996 and amended in 2011. Only Muslim male descendants of Qaboos’ great-great-grandfather Sultan Turki (r. 1871-88) who are legitimate sons of Omani Muslim parents are eligible to become sultan. When the throne is vacant, the Al Sa‘id Ruling Family Council is required to meet within three days to designate a successor. If the members of the Family Council fail to choose someone, the Defence Council, together with the chairmen of both the Consultative Council (the elected Lower Chamber) and State Council (the appointed Upper Chamber), along with three Supreme Court members, confirms the person designated beforehand by the former ruler in a letter addressed to the Ruling Family Council. In 1997, Sultan Qaboos announced that he had ‘already written down two names, in descending order, and put them in sealed envelopes in two different regions.’

Sultan Qaboos (r. 1970) has no children and has not publicly designated an heir in 2014. The principles of succession to the throne are formalised in Articles 5 and 6 of the Basic Law of the State, promulgated by royal decree in 1996 and amended in 2011. Only Muslim male descendants of Qaboos’ great-great-grandfather Sultan Turki (r. 1871-88) who are legitimate sons of Omani Muslim parents are eligible to become sultan. When the throne is vacant, the Al Sa‘id Ruling Family Council is required to meet within three days to designate a successor. If the members of the Family Council fail to choose someone, the Defence Council, together with the chairmen of both the Consultative Council (the elected Lower Chamber) and State Council (the appointed Upper Chamber), along with three Supreme Court members, confirms the person designated beforehand by the former ruler in a letter addressed to the Ruling Family Council. In 1997, Sultan Qaboos announced that he had ‘already written down two names, in descending order, and put them in sealed envelopes in two different regions.’

To a large extent though, the complexity of the mechanism, combined with the central role played by members of the Defence Council, of the Supreme Court and chairmen of parliamentary councils, none of them belonging to the royal family, raises many questions. There is every indication that the Ruling Family Council has never met to date. In these circumstances, if the royal family cannot make a decision, up to what point is it ready to be deprived of supreme decision making by individuals who do not belong to the Al Sa‘id family and who owe their position to Qaboos only? Moreover, in spite of the precautions taken by the ruler, is there not a risk of contradictory messages emerging, a situation which would involve political confusion? In Qaboos’ absence, there does not seem to be any patriarchal figure in the Al Sa‘id family who could oversee the succession process and ensure that disagreements remain contained.

This only makes the succession more open. The highest personality in official protocol, Sayyid Fahd bin Mahmood (b.1944), Deputy Prime Minister for the Council of Ministers, whose children’s mother is of French origin, does not seem to be able to claim the throne since he cannot plan to pass the kingship to one of them after his death. Moreover, the Minister of Diwan of the Royal Court, Sayyid Khalid bin Hilal, does not belong to the lineage of Sultan Turki. The more probable candidates are thus the three sons of Qaboos’ paternal uncle and former Prime Minister (1970-1) Sayyid Tariq bin Taimur (d.1980).

Former Brigadier-General Sayyid As‘ad bin Tariq (b.1954), a Sandhurst graduate who briefly held command of the Sultan’s Armoured Corps in the 1990s, has been the Personal Representative of the Sultan since 2002. His half-brother Sayyid Haitham (b.1954) served as Undersecretary, then Secretary-General, in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and became in 2002 Minister of National Heritage and Culture – the position he currently holds. Former Rear-Admiral Sayyid Shihab (b.1955), a full brother of Haitham, was appointed in 1990 as Commander of the Royal Navy of Oman, and then served as Adviser to the Sultan since 2004 and chairs the Research Council.

All of them have been very active businessmen too. As‘ad has been the chairman of the board of trustees of Oman’s first private university, University of Nizwa. He runs several companies, including Asad Investment Company, operating as his personal investment vehicle and said to control more than US$1 billion in worldwide assets. His son Taimur (b.1980), who is married to Salma bint Mustahil al-Ma‘ashani, the daughter of Qaboos’ maternal uncle, is considered to be the leading candidate in his generation for the succession. While holding the position of Assistant Secretary General for International Relations at Oman’s Research Council, Taimur served on the board of directors of the fourth Omani bank, Bank Dhofar, until 2011. He has been chairman of Alizz Bank, Oman’s second Islamic bank, since 2012.

Haitham is chairman and the main shareholder of National Trading. The holding has been involved in the construction of two major power plants (Manah and Sohar) and is an agent in Oman for several multinational companies. Haitham was also involved in the Blue City project, a mega tourism-devoted new city south of Sohar, initially worth $20 billion which was supposed to accommodate 200,000 residents by 2020. However, mismanagement and a legal battle between the project’s owners, with the 2008 regional real estate crisis on top of it, resulted in the necessity for the state’s sovereign fund, Oman Investment Fund, to buy a substantial amount of Blue City bonds in 2011 and 2012. Since December 2013 Haitham chairs the main committee responsible for developing and drafting the new long-term national strategy entitled ‘Oman Vision 2040.’

Shihab has a number of business interests too through the group of companies he owns and chairs, Seven Seas, which has invested worldwide in petroleum, mutual funds, properties and medical supplies. In particular, his company AMNAS has been granted by royal decree in 2003 the exclusive rights to navigational aids in Oman’s territorial waters.

The 1996 Basic Law ratifies a paternalistic conception of a state whose guide is the current sultan, who concurrently holds the positions of Prime Minister, commander in chief of the armed forces, Minister of Defence, Minister of Foreign Affairs and chairman of the Central Bank. The triptych encompassing since the 1970s Oman’s ‘Renaissance,’ the state apparatus, and its supreme figure, Sultan Qaboos, cannot be touched without putting into question the entire nation-building project. This model of legitimacy, based on the extreme personalisation of the political system, is intimately linked to the person of Qaboos and to him only. Besides the tremendous social and economic challenges that will await Qaboos’s successor, no doubt young Omani society is unwilling to grant him the same degree of authoritative paternalism as their parents did. As a matter of fact, the ‘Omani Spring’ has already revealed how this model has long since reached its limits. The sultan’s reluctance to break the taboo on key issues, notably the appointment of a Prime Minister and establishing the foundations for governance of a post-Qaboos Oman, has only fuelled widespread anxiety. This brutal collision with reality confronts the Omani regime with questions which, if not soon answered by Qaboos, may provoke considerable turmoil in the event of his sudden demise.

Marc Valeri is Senior Lecturer in Political Economy of the Middle East and Director of the Centre for Gulf Studies at the University of Exeter. He is the author of Oman: Politics and Society in the Qaboos State and co-editor of Business Politics in the Middle East.